Outlands Scribes Handbook

Please note that the following article on papers, inks, and paints is intended as a guide. It represents its contributors' best advice for doing calligraphy and illumination which is intended to last, and to provide information on which materials and techniques work to the best advantage.

Permanence

Permanence in an artist's pigment means that it will not be altered during the life of the work of art in which it is used, by any condition which it is likely to encounter. Light accelerates the breakdown of some pigments while others are virtually untouched. These latter pigments are called "light-fast". When the term "permanent" is used, it indicates that the material is not only light-fast but also that it will not be altered by other conditions such as heat, humidity, and the normal reactive gases found in air. For example, the ultramarine blue prized by medieval artists is extremely light-fast but may be destroyed by exposure to weak acids which may be found in urban air. Other examples may be found in some of the gold metallic paints and markers which over time will turn green on exposure to air. As artists, scribes and calligraphers are encouraged to be aware of the quality of the materials they use. Some companies have rated their paints and pigments for permanency and, more recently for light fastness. Winsor & Newton classify their materials as follows: AA is extremely permanent; A is durable; B is moderately durable, and C represents fugitive colors. Holbein gouache is classified for permanence with *** being the most permanent, and no asterisks being the least. The manufacturer of the paint generally will have a materials sheet available, listing the pigments used in their paints, and the permanency and opacity of each one. If this sheet is not on display at the art store, ask to see it, sometimes they are kept behind the counter.

Testing for Light-Fastness

If no information is available on the light-fastness of the paints or inks that you have, it is possible to conduct your own test. This will take some time, but is a good way to find out which of your materials will stand up to the light, and hence will still look good in many years. Take a piece of paper of the sort you will be making scrolls on, and paint stripes of each color at least a couple of inches long. It is helpful to label each stripe with the brand of paint or ink, and the name of the color. Now cut the paper in half, splitting each stripe about evenly. Take one half, and put it in a dark place such as a drawer. This is the control for your experiment, and will show you what the paints originally looked like. Take the second piece and tape it in a nice sunny window. Leave it in for as long as you wish. Two weeks will reveal any fugitive colors, several months of exposure will reveal those that will fade over a longer period of time (years of normal exposure). Compare your exposed paints to the ones that have been stored in the dark to see the effect.

Health and Safety

Some of the materials artists use can kill or cause illness. Avoid putting them in your mouth, breathing airborne dust such a dry pigments, and avoid skin contact.

Good Working Practice

Below are a few general tips which you should adopt with all art materials whether hazardous or not. These suggestions should be supplemented by the more detailed instructions which appear on product considered to represent particular risk of adverse effect.

- Do not eat, drink, or smoke while painting.

- Wash hands thoroughly after painting.

- Do not "point up" brushes by wetting the hair with your mouth.

- Provide plenty of fresh air ventilation and circulation in the studio or classroom. Whenever possible use an exterior vented exhaust system.

- Keep all materials, and solvents in particular, well out of the reach of small children.

- Keep all materials, and solvents in particular, tightly capped when not in use.

- Do not pour out more solvent than is necessary for a single painting session.

- If paint, or solvents in particular, are splashed onto the skin, thoroughly wash the affected area.

- Refrain from applying paint with your fingers.

- Avoid prolonged inhalation of paint and solvent fumes.

- Never sleep in your studio without first removing painting materials to another room and in particular, be sure to dispose of all unused solvents.

- Clean up all spills.

- Store soiled painting rags and disposable palette sheets in an airtight metal container. Better yet, dispose of them in an appropriate manner.

- Do not expose solvents or paints to open flame or excessive heat sources.

- When using powdered pigments or paint, or when spraying paint ( i.e. when airbrushing) take great care to avoid inhalation preferably by the use of NIOSH approved face masks or respirators.

from: Artist's Materials (Piscataway, NJ: Windsor & Newton, Inc.), p. 111.

Inks

Calligraphers have many choices of inks. Chinese, Japanese, or India inks are carbon based and light-proof. These come as sticks, which need to be rubbed with water in a shallow mortar, or in bottles already liquefied. Iron gallotannate writing inks also were used during the middle ages. These inks work by the reaction of oxygen from the air on an acid mixture of iron salts and tannin (obtained from nutgalls). Because this reaction takes a day or more to complete, a dye is added so that fresh writing is visible. Iron gallotannate inks are not light-proof.

Colored Ink

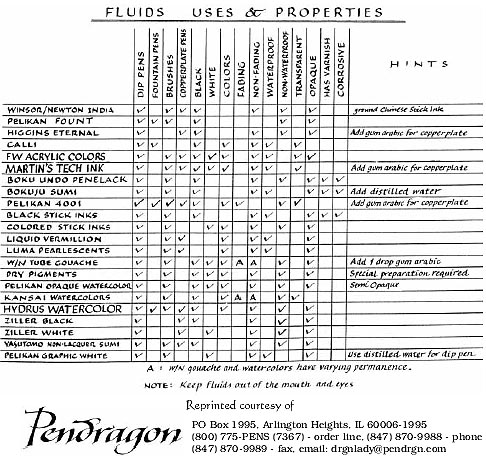

Colored inks need to be used with discretion. Many colored inks which are based on soluble dyes are not light-fast. An example of this is Winsor & Newton drawing inks (except black, white, gold, and silver). In a test of light-fastness, blue Higgins drawing ink was noticeably faded in just three days exposure to sunlight (through glass), and it was completely gone within two weeks. Other colored inks, such as FW's, are light-proof. Please consult the Fluids Uses and Properties chart below for information. Please note that Pelican 4001 is not light-proof.

When using colors in a pen, the preferable way to work is to mix your own colored ink from gouache of known good permanence. To do this, squeeze about a pea-sized bit of gouache from its tube into a mixing tray. Then add 1 or 2 drops of gum Arabic or glair as a binder (note: not all gouaches mix well with glair). Then add water a drop at a time while mixing until the solution is thin enough to flow through the pen. Stir the ink with your mixing brush each time you load the pen as the pigments may tend to settle. Because of the thickness of this ink, it may not flow well with the reservoir attached to the nib. Also, the slope of the writing surface can be reduced to help the ink flow out of the pen and to prevent the ink from pooling in the feet of the letters.

There are some pre-mixed colored inks with a good light-fastness rating, but unless they appear on the chart below, it is highly recommended that you test them yourself for permanency, as explained earlier in this section. Some inks, even those labeled as "permanent" will fade when exposed to light.

Please avoid using ink colors that you don't see used in period manuscripts. Colors of lettering that are fairly common in medieval manuscripts include red, green and blue. Colored lettering is almost always used only to emphasize certain words or letters, and virtually never makes up a significant part of the body text. Having the body text in a bright color such as pink or turquoise is a sure way to ruin the period look of your scroll.

Fluids chart:

Paints and Pigments

Paints may be grouped into the following categories:

- Watercolors. These are composed of pigments finely ground to a nearly transparent consistency in a water solution of gum. Because of the transparent characteristics of this medium, it behaves almost like a stain. They generally include additives such as wetting agents and preservatives.

- Gouaches. These are opaque colors that use the same pigments as watercolors but have a better ability to cover underlying layers. Because they are opaque, they can be used to paint light over dark (great for highlighting). The paints can be reworked after they have dried, and are not waterproof. Gouache is generally the best type of paint for most scrolls.

- Acrylics. These paints are made of pigments mixed into an acrylic emulsion. Like watercolors and gouaches, they may be thinned with water. When dry, these paints are waterproof. They tend to have a bit of a plasticy look to them when dried. Because they are waterproof, it is important to keep the paints wet by spritzing them periodically while you are using them.

- Acryla Gouache. New in the past few years is a type of paint made by Holbein, called Acryla gouache. It uses an acrylic binder which can be thinned with water, but dries to a matte finish much like gouache. It is waterproof, like acrylic paints, once dried.

- Dry Pigments. These powders are the basis for all of the above paints. They may be ground into various binding agents to make watercolor, gouache, or oil paints. Glair (made from beaten egg white) will also serve as a binder.

- Oils and Alkyds. Oil paints are made from pigments ground together with drying vegetable oils. Alkyd paints are made from pigments mixed with an oil-modified alkyd resin. Because of the long drying times and the oil-based binders, these are not used for SCA scrolls.

Writing Surfaces

There is a vast array of papers and other writing surfaces available to the scribe today. In period, virtually all manuscripts were produced on vellum or parchment. Paper was used in period, but it was considered inferior in quality to parchment, and so was not generally used for manuscripts. In 1494, Trithemius, Abbot of Sponheim wrote: "If writing is inscribed on parchment it will last for a thousand years. But if on paper, how long will it last? Two hundred years would be a lot." Papyrus is another period material that could be used to make a scroll. In the Society, there is no limit to what scrolls can be made from, provided that you use durable materials that look period and will not decay during the lifetime of the recipient. See section on Paper for a list of sources for various papers and other writing surfaces.

Parchment and Vellum

Parchment and vellum are made from the specially cured hides of animals. Vellum is made from calfskin, and parchment can be made from any animal, although it is most often sheep or goat skin.

The production of parchment or vellum is a time-consuming and laborious process. Parchment has always been a very expensive material, both in medieval times, and today. A piece large enough to produce a scroll will cost a minimum of $20 for a small scroll, on up to $150 or more for a very large one. When it comes to buying parchment, there can be some confusion about the terms "parchment" and "vellum" because both of these terms have been adopted to refer to other types of modern writing surfaces. "Vellum" sold in art stores is most often drafting vellum; a type of mylar sheeting used for drafting with technical pens. Plastic film is obviously not suitable for SCA scrolls. "Parchment" can refer to any of a variety of types of paper, from the mottled parchment-look paper that we see sold for calligraphy, to "parchment paper" used for wrapping food during some types of cooking. While it is fine to use the mottled parchment-look papers, find out if they are archival quality before purchasing them. Many are very acidic, and will yellow and become brittle over the years. If you wish to use genuine parchment or vellum, your best bet is to look for suppliers on-line. It is not carried by art stores in the Rocky Mountain region.

Paper

Paper is the most common of materials used to receive writing. The Chinese were the first to produce paper in about 105 A.D. In 713, it entered the Arab world carried by Chinese prisoners of war. The secret of its manufacture spread to Baghdad in 793, Egypt in about 900, and Morocco in 1100. Shortly after the Moorish invasion of Spain in 711, paper making began in Europe. Paper was manufactured at the mills in Fabriano, Italy in 1276, in France in 1348, Germany in 1390, Flanders in 1405, Poland in 1491, and in England in 1495. From within the Byzantine Empire, the earliest extant manuscript copied on paper is from 1105 and the earliest surviving paper document is a chrysobull of 1052.

As artists, scribes have a duty to understand that their work may last only as long as the material on which it is written. If this material is paper, its longevity is determined not only by its being handled properly, but also by the effect of environmental factors such as light, temperature, humidity, and atmospheric gases on components of the paper. The primary reason for the deterioration of modern papers is the acidity within the paper. This acidity may be due to the method of manufacture or the presence within the paper of lignin which is composed of organics that break down under light and heat to form acidic compounds. The acids within paper cause it to yellow, become brittle and eventually disintegrate. The pH value is a description of acidity. A low pH value represents an acidic material; a high pH indicates an alkaline material, with pure water being neutral at a pH of 7. A paper that is non-acidic or has a neutral pH is to be preferred for permanent artwork over an acidic paper.

Papers may also be described as buffered. This indicates that the paper contains an alkaline additive. Among conservators, the current preference is for buffered papers which can remain non-acidic in the presence of an acidic environment such as polluted air or acidic mat boards as long as the buffering agent has not been neutralized by its surroundings.

It is not simple to measure the acidity of any given paper. Avoid yellowed fake parchments (unless they are sold as archival quality); they are frequently manufactured with acid to make them yellow. A pH indicator marker (available from book arts suppliers in Appendix 4) is useful in determining the approximate pH of a white paper but may not be appropriate for natural cream-colored papers.

The papers listed below are those which are sold as a.) 100% rag, b.) neutral pH, c.) buffered, d.) acid free, e.) archival, or f.) acceptably archival:

Arches Text Wove

Arches Watercolor, various weights, both hot and cold press (hot press is smooth, and is best for calligraphy, 140 lb. is the best weight, although 90 lb. is also acceptable).

- Archival Parchment

- Bodleian

- Canson Mi-Tientes

- Coventry Rag

- Diploma Parchment

- Fabriano Roma, Artistico

- Folio

- Lana Laid, Lanaquarelle

- Pergamenata (an acid-free parchment look paper from Italy)

- Stonehenge

- Strathmore

- Velazquez

- Waterford/T.H. Saunders

Many hand-made papers are also of good archival quality. Ask the person supplying the paper about its archival characteristics. This would not include papers containing large pieces of plant material such as leaves or flowers.

The information contained in this list was compiled from the catalogs of Daniel Smith, PaperSource, and Pendragon. It is not intended as an exhaustive list of acceptable papers.

Reprinted courtesy of:

PO Box 1995, Arlington Heights, IL 60006-1995

(800) 775-PENS (7367) - order line, (847) 870-9988 - phone

(847) 870-9989 - fax, email: drgnlady@pendrgn.com